Karaburma

Today, Karaburma is an urban neighbourhood in the Belgrade's Palilula municipality, with some 35,000 inhabitants.

The original toponym used to be Kajaburna, from Turkish words kaja (= rock) and burun (= nose, cape) – that is, „rocky cape“. A corrupted version of the name – Karaburma – became dominant in the second half of the 19th century, helped by folk etymology which relied on Turkish words kara (= black) and burma (= ring), i.e. „black ring“. This version stuck because from the 1860's to 1902, Karaburma was the place where people sentenced to death by the Belgrade courts were executed.

The place for executions was a slope close by where the Pan

evo Bridge stands today.

That is where the graves would be dug on the eve of an execution and stakes fixed in them to tie the convict to. On the execution day, Karaburma would be teeming with crowds, including children, who came to watch the shooting. After execution, the body would be untied from the stake and the grave quickly filled in with earth.

assassin Kne~evi� standing above his grave in Karaburma, 1899

In time, a sizable cemetery was formed in Karaburma, with several hundred unmarked graves. The relatives were only exceptionally allowed to mark the grave of an executed convict. For example, a stone with an engraved cross was placed at the spot where the fourteen conspirators who plotted the assassination of Prince Mihailo Obrenovi� had been shot on 16 July 1868.

After many executions, „Karaburma“ became (and remained to this day) a synonym for the death penalty and, more generally, for any bad end. „So-and-so shall end in Karaburma“, was often told of bad men and naughty children. The criminals would talk of Karaburma as their fate. In 1898, a robber under investigation said wistfully: „I guess I shall fill a hole in Karaburma before the Spring“. In 1912, two „male ladies“, i.e. two transvestites, arrested for attending a party in Belgrade dressed in drag, told a journalist rather dramatically (in view of the fact that they were under no threat of capital punishment): „We would prefer Karaburma, so that it all would be over“.

The last judicial execution in Karaburma took place in 1902, although the Austrian military authorities did erect gallows there during their occupation of Belgrade in December 1914. Nonetheless, Karaburma remained a „haunted“ place for long and various superstitions grew in its legend. Soon after the fourteen conspirators were executed in 186, a thunderstorm hit Belgrade and it was widely believed that their grave was struck to show the Wrath of God. In 1908, a police patrol claimed that the graves were haunted at night by „a girl in long white dress with hair flowing down her back“.

The execution grounds had been excavated twice in the course of urbanization of the area: in 1912 and 1925. On both occasions, the diggers found remains of those executed – the fourteen conspirators were dug out in 1925. A new settlement was built there: in 1932, it had some 7,000 inhabitants, mostly poor, and no water or sewage. They petitioned the city to have the name changed, as they wished to get rid of the stigma of „Karaburma“.

Not only men, but dogs as well – and for much longer – were executed in Karaburma. Until the 1930s, the „Dogcatchers' Quarter“ stood close to the old execution grounds. It was a slum where the city's skinners found a refuge. Under a contract with the City Hall, they caught stray dogs, took them to Karaburma and, if no owner claimed them within three days, killed them (with an axe), selling the hides at five dinars apiece (used to manufacture gloves).

In mid-1930s, a modern dog pound was built in Karaburma: it was hoped to kill the dogs there „humanely“ – by electrocution. But the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals kept petitioning the authorities about the ghastly treatment of dogs in Karaburma.

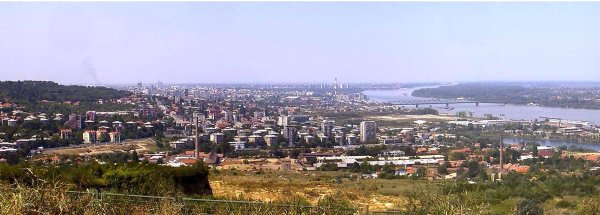

In the Fall of 1935, the first tram passed through Karaburma on a newly opened line: The Monument – The King Peter II Bridge – The New Cemetery. And this is how Karaburma looks today: